Fighting Genocide Through Needlework

An interview with Lina Barkawi, a Palestinian embroidery artist, on opposing the war on Gaza and challenging the world's biggest embroidery company.

In the summer of 2020 I took up embroidery, which I became a bit obsessed with amid the distress of covering the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and racist police violence. It’s been some time since I really got to enjoy embroidery — probably not since the end of 2021, if I’m being honest. But I still keep up with the embroidery community on Instagram, just a handful of creators I followed in 2020, and then some of the craft suppliers, like the globally-recognized DMC (short for Dollfus-Mieg et Compagnie).

It was only by my casual enthusiasm that last month, I noticed the DMC account had published an interesting statement about Gaza and Palestinian embroidery, a style known as Tatreez. Not that it said much in terms of substance, but it had been some time since I’d actually seen a company post an earnest “we’re listening” graphic a la 2020.

I had no understanding of what caused DMC’s content managers to seem to care about the genocide in Gaza (well, “conflict,” the post stated), but it seemed generally positive, and potentially organic.

It wasn’t until a few weeks later, when DMC posted some “educational” Palestinian embroidery material online that were meant to function as their official statement on Gaza, that things clicked in place. Another company, their feet held to the fire, giving a half-assed statement about the genocide of a group of its customers, with very little if any reference to the customers or the genocide itself. An empty consolation.

A few taps on my screen and I found the Instagram account of Lina Noor Barkawi, a half-Palestinian, half-Panamanian Palestinian Tatreez artist in New York City who, I learned, had helped launch an open letter from the online embroidery community. The letter called for DMC to make an official statement supporting textile crafters in Gaza and Palestine amid Israel’s genocide on Gaza.

Earlier this month, I talked with Barkawi about this community effort, and DMC’s utter ignorance in response. Barkawi teaches Palestinian Tatreez to other Palestinians in the diaspora through her courses on “Lina’s Thobe,” helping students reclaim this ancestral art of embedding themselves and their stories onto a traditional looking dress using embroidery, known as a Palestinian thobe.

In our interview, Barkawi talked about the online embroidery community’s fight for recognition of Palestinian textile artists and of the genocide and Gaza, and the larger fight for the preservation of indigenous textile art in the face of colonialism.

“Since 1948 there have been some shifts in the practice itself, so I'm trying to go back to the pre-1948 practice of doing it for yourself, by yourself, that's purely an expression of yourself as opposed to a form of income or explicitly national identity,” Barkawi told me. “Those are themes that have come up because of the ongoing occupation of Palestine.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is the Western understanding of cross stitching or embroidery?

If you’re an embroiderer, you usually know what cross stitch is. It's pretty basic. So many cultures have their own cross stitch tradition. I learned it from my Panamanian mother. Latin America uses cross stitch a lot, and this was my experience before I learned about Tatreez later on.

The word “Tatreez” literally translates to embroidery. There have been up to 16 types of embroidery techniques documented in Palestinian embroidery, but the one that everyone recognizes is the cross stitch, because it creates these motifs.

People's perception of cross stitch is more like creating images out of the stitching. Like when you go to a Michael’s [craft store], there's a ton of cross stitch kits, and they're going to be imitating pets or faces. And then there's a lot of people who do more real-life [imagery]. Those involve a gajillion colors, and it's really intricate, so it’s a lot of counting [rows and stitches].

That's why I like Tatreez, because it's actually an easier way to approach cross stitching. There's five colors that you use at a time. The motifs are pretty geometric, so it's easy to repeat over and over again. You don't have to think about it.

So what sets Palestinian Tatreez apart from other styles of embroidery?

I think someone can say “Tatreez,” and everyone associates Palestinian embroidery because of the library of motifs used in the cross stitch. The library is really important because it depicts the experiences of women on their land. Historically, it's a reflection of Palestinian life. It's very “plug and play,” so you can take the motifs that mean something to you, or the ones you really like, and you can make a combination of your own. It's completely unique, but it's using the same library of motifs. You'd still know that it's Palestinian, but it's a completely different arrangement. And that's what's unique about it and why Tatreez is so well known, because it's very recognizable because of the different designs.

[Tatreez] being a library, it's also a language. Women can use this library as a way to tell stories, and they tell stories of their indigeneity. So everything is connected to the things they're witnessing outside, things they're engaging with, their day-to-day lives. This was rooted in a farmer's environment, so historically it was practiced primarily by those who were very much tied to the land. That's very much reflected in the designs, because it's depicting birds, and different trees and plants, and things like that.

It's so important because there have been all of these stories documented over time, but they just haven't necessarily been translated for the rest of the world. I think that's the role I want to play – helping Palestinians reconnect to their culture through this language, and helping them to tell their own stories.

Can you tell me about the relationship between the DMC thread company and the art of Tatreez, prior to the open letter?

[DMC is] the thread that everyone uses in general. I think globally, they are the most well known. They aren't a monopoly exactly, but they have the best quality threads of the West. They have a catalog that is consistent. [Their threads] don't fade, and they don’t bleed in the wash. So they have just a fantastic reputation.

As I was doing my [own] Palestinian thobe, I was doing a lot of research. I had learned DMC was introduced to the region around the 1920s, and then became the de facto producer of threads for Palestinian embroidery. Before that, the thread was hand dyed. It wasn't consistent. It was limited in colors because they were using natural resources to dye the threads, they were also using silk threads, so it wasn't as strong of a thread. DMC has a really strong product and they entered the market and they flourished. Palestinians exclusively use DMC thread, this is what I had come to learn.

And in the West, a lot of people primarily use six-strand floss. But in the Middle East, everyone uses the size eight thread balls. In the U.S., they're really hard to find, and you have to order them online.

What pushed you to start organizing for DMC to openly recognize the work of Palestinian fabric artists?

[DMC and Palestine] had crossed my mind before because when [Russia invaded] Ukraine, there was an email sent to the DMC listserv sharing “We stand with Ukraine.” And not even just DMC – a lot of embroidery groups were doing Zoom sessions on Ukrainian embroidery, emphasizing that we need to support our Ukrainian brothers and sisters.

I had no problem with it, obviously. But like in my mind I'm like, Palestine Tatreez has been around for forever. Yet, I've never seen anyone in the embroidery world [speak up about] this. The West doesn't realize that we have this very rich embroidery tradition. That has been happening in my mind over the last few years.

And with everything happening in Gaza, and not a word from DMC – how have they not spoken up yet? The embarrassing part is that we exclusively use their products. That's the part that really got to me. I was like, why would we ever use this company that never says a word about Palestine?

A few weeks ago, I started vocalizing this [concern] in safe spaces and Facebook groups that I'm in. While visiting a friend, I shared my idea with a friend of hers who's a fantastic writer, and she helped me write the letter. I initially started with sharing it in Facebook and WhatsApp groups, and other spaces I'm in with Palestinian Tatreez artists. And then I started talking to allies online too. I think it's because of [their] reach that it got DMC's attention. Because the Palestinians are great, but I don't think DMC cares. But when they see that people are united globally, and it's stitchers from all over the world, and people who have a very large following, that gets their attention.

How did DMC initially respond to the open letter?

I was surprised that they responded so quickly. The goal at first was 1,000 signatures. We have almost 6,500 at this point.

They put up their first post, and it gave me a lot of hope. It said we're working behind the scenes. What does that mean? I wanted to make sure that they have the opportunity to collaborate with Palestinian artists who are experts in this space. And so I emailed whoever I could find addresses for, and I attached the open letter and all the signatures. It was a 150-page document. And then in the email itself, I gave them all of the resources. I'm giving you everything on a silver platter. You don't need to work with me. You can work with all of these other people who are known experts and who have done their research and have documented everything of this art form. Please collaborate with them.

The CMO responded within 24 hours. He's like, thank you so much for bringing this to my attention. He said, “I personally am excited to collaborate with Palestinian artists.” He came back to me in a couple of days, and he was like, here's what we're suggesting. What do you think?

And what they suggested was honestly high level, but it was in line with what they had done with Ukraine. It was a donation to the Red Cross, it was free patterns in their online library.

I responded, this is fine, just a few things that I would take into consideration: when you're doing those free patterns, make sure you are collaborating with Palestinians who have those patterns. I also said, be careful with your language. It's not a conflict. It’s a genocide. And this isn't just people in Gaza, this is a Palestinian art form. And I called out the few pieces that I thought were inaccurate and needed to be rethought. I said I would expect you to also send [your response] in an email to your email listserv. I want everybody who buys your products to know that this is where you stand, and these are the resources that DMC has available to them to learn more. He never responded. That was two weeks ago.

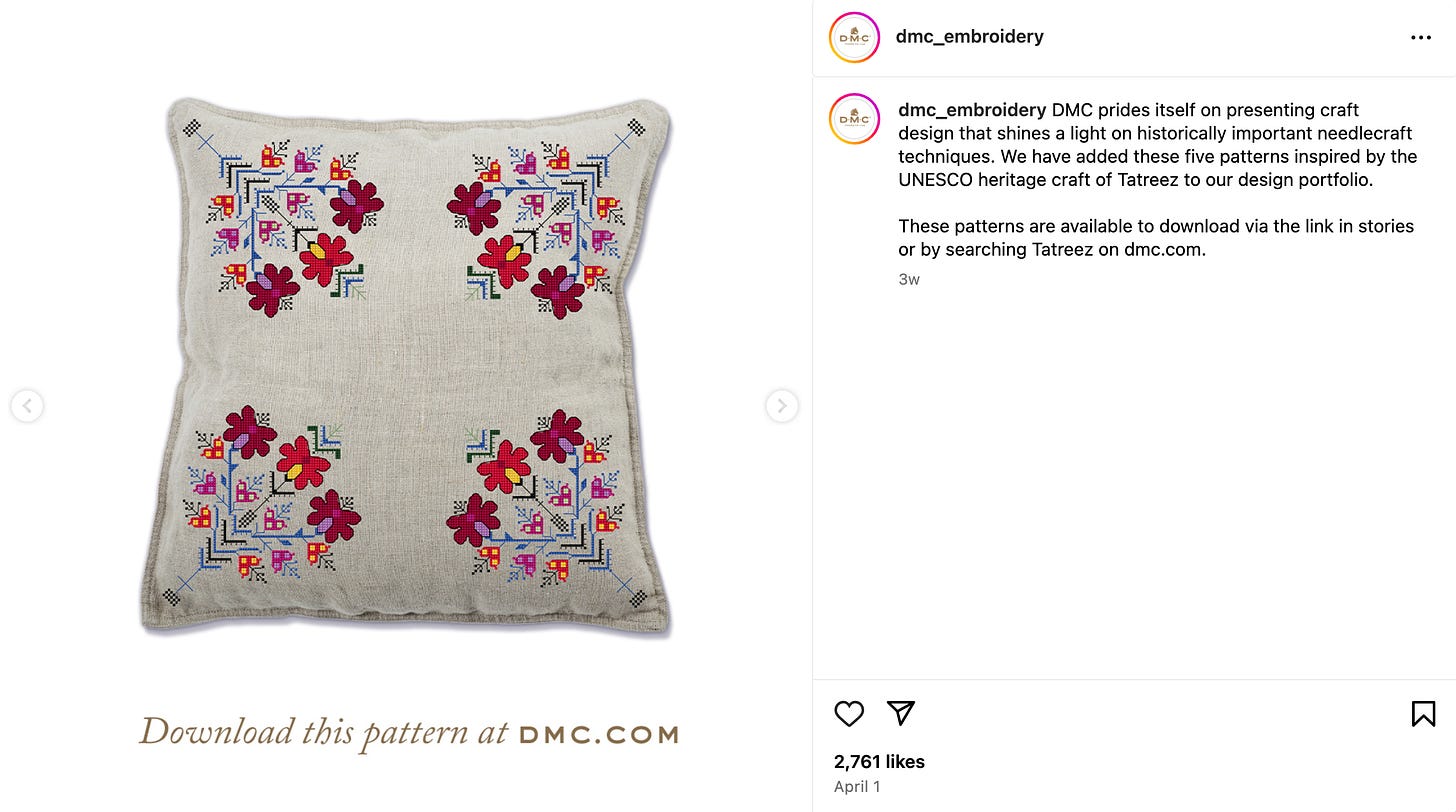

And then they posted this response, which was so tone deaf. It feels like he just told somebody on his team, do a little bit of research, put it together and just post it. And it doesn't seem like they did any research. Two of those patterns are not Palestinian. I've never seen those motifs before in my life.

The verbiage is off. They don't even use the word “Palestine” or “Palestinian” in their main description of the patterns. They just say the word “Tatreez” and they mention “UNESCO” over and over again, they do not say that it's Palestinian. Tatreez, again, translates to embroidery. You need to be explicit saying “Palestinian embroidery,” and this is why it's unique, etc. And I provided them with all of that context. If you had just opened it, you would have learned very quickly what this is about. And none of that was incorporated in any of their copy.

It was the same day as the Al Shifa Hospital atrocities that came to light, so I waited until the next week to email the CMO, being like, this is ridiculous, here's why it's ridiculous, and FYI, the community is watching. And then yesterday, there was another post by the Tatreez and Tea Instagram page – she's a Palestinian dress historian and the teacher I actually took my first class with. She has written a couple of books about Tatreez. She connected with a bunch of people who are in the community who are known experts of Tatreez. And they came out with this united post talking about what's wrong with the response DMC put out.

I looked at the language very closely and they never mentioned “Palestinian embroidery.” They only say that these patterns are “inspired by” designs provided by the Palestinian Culture Center in Jordan, a line they seem to have added to the description after first sharing the designs. Had you included that group in your list?

I don't even think I included them. I included people who are writers and researchers. For example, the Tiraz Centre is huge. They've acquired all these dresses and have done all this research and preservation of the art form. But I am curious about two of the designs, because these do not appear to be Palestinian. So where did they get the inspiration from?

Tatreez, as I mentioned, is this library, a language, but it's also very localized. Before 1948, you could literally tell where someone is from based on the motifs that they were using, and so for them to not [point] that out in their free patterns… Gaza has a very big part of that library. They could have called that one out more specifically because of what's happening right now. That would have been a good move, that would have shown us that you had taken the time to learn about the art form and curate something that actually educates your following – not just to say you did this.

Given that these free “Tatreez” patterns are based upon designs shared by the center, you mentioned that the last two patterns do not appear to be Palestinian Tatreez. I think I can visually understand why, but can you explain why?

The first one and the second one 100 percent look like Tatreez. The third one, there are definitely elements of this that look like Tatreez, like some of the borders are definitely motifs that we have existing in our library.

The other two I don't recognize. The fourth one, that flower, is not familiar to me at all. Just that one border in between the two looks like it's a feather motif.

And the last one is the one that's the most laughable because it doesn't even look like it's all cross stitch, and we don't use that technique.

They can say it's inspired at all they want, but it's not Tatreez.

I’ve looked at the website and the difference between the patterns they put out for Ukraine and for Palestine is obvious. All the Ukraine designs say, “Stand for Ukraine,” “Peace in Ukraine,” “Stop War in Ukraine.” If they really wanted to make some sort of statement, they could have done designs such as this around Palestine, even with images like the flag or the watermelon. It's like, why speak so loudly when you are so wrong?

That's what we're all baffled about. You're clearly trying to appease people, but you're doing it in such a poor way. If you really didn't care, I would just be quiet. Otherwise, why waste your time? My new hypothesis is that their Middle East business is actually pretty significant. But the fact that they did not mention the word Palestine [when talking about Tatreez] blows my mind. Just a very direct way of erasure. Also, they don't mention Gaza in any of the new content. It was just in that first [post]. So my activism is not over – we're not done.

So after this bullshit response, where does the online Tatreez community go from here?

I think the obvious route would have been a boycott. The problem is there is no [thread] alternative. And honestly, I think that's maybe a good thing. This forces us to apply more pressure. I personally feel like I've given them enough leeway. There are more [conversations] happening on Instagram and I want to see if that does anything. But I would like to email all the people who signed the open letter and be like, thank you for signing, your signature has been included and sent to DMC, here's how they responded, here's why it's wrong, and here is a template for you to complain to them yourself.

I want people to spam them with the email. Because really these corporations, it's about their bottom line. So you have to make them feel like their customer base is going to turn, and there's no better way to illustrate that than a lot of emails on a Monday morning.

(Note: As of this publishing, DMC has still not responded to follow ups from Barkawi or other Tatreez artists. In a follow-up email Barkawi shared, “I have no other updates from DMC. They posted those very insensitive posts and haven't said a word since. We've sent a ton of emails asking them to do better and as far as I know, they don't plan on doing anything. They also never sent an email announcing these free ‘Tatreez’ patterns or donating towards Red Cross which just tells me it was all to appease their followers on Instagram.”)

Connecting this to the broader global resistance to Israeli occupation and the genocide on Gaza, where do you feel that the work of Tatreez artists fits in?

I think in a direct way, we're helping to spread the word within the embroidery community globally. I've had so many conversations now with people who had no idea. One of my students messaged me being like, during these last few weeks this [thobe course] has been the best thing that I spent my time on, because every weekend when I'm working on this project, people ask me what do I do for the weekend, and all I do is talk about Palestine. There is something really powerful about having something that's art be the thing that brings up Palestine because it can be more palatable to the person who is still like “both sides.”

What's crossed my mind in the last couple of days in particular is this idea of boycotting DMC. I just had a conversation about it with another Tatreezer, and we do not see the Palestinian or Arab community boycotting DMC anytime soon because their quality is so good. And I think what's unique about Palestinians in the diaspora who appreciate the art form and come to it of their own accord, is that we do our due diligence on researching the origins of the practice. And one of those things is this idea that Palestinian women have been doing this before DMC was in the region.

Why not consider creating a competitor to DMC? Why does it have to be a “boycott for somebody else”? Why can't the people of Palestine create their own thread company or their own economic systems that provide these types of products that are so rooted in our culture for ourselves. And I think it's because people back home are too preoccupied with occupancy. They're trying to survive. And that's where the diaspora can really play a role.

Within developing this letter, have you noticed a united stance on the ending of occupation versus a permanent ceasefire across the Palestinian Tatreez community, or is it varied?

I would say before this genocide, it was varied. People were not really sure what a post-occupation could look like, and so it would have been varied. I think with this genocide, people are a lot more on the same page, and in that it's not just immediate permanent ceasefire, it's also full liberation. Ceasefire first, then end apartheid, then end occupation.

Is there anything else you want people to know about Palestinian Tatreez or DMC?

This isn't meant to be a Palestine-only struggle. Yes, there is an immediate urgency around what's happening. But this is a bigger conversation. This is a bigger fight for recognition of Indigenous practices that have always been erased on behalf of the colonizers, and a lot of communities have those experiences. This is a global struggle. I'm hoping that it makes people start thinking about: what about other traditions? What else has been bombed off this planet? What else has been erased? And what can we recover and start to preserve better?